Machine-precise Verification of Lustre Specifications

In this post we show how to use Intrepyd (repo) to translate and verify Lustre specifications. The translation is such that the semantic is machine-precise, i.e., we verify properties by taking into account finite integers and floating-point representations for integers and real variables respectively, which is something that, to the best of our knowledge, is not available even in commercial tools. We compare Intrepyd with an existing tool, Luke, on the integer part (as Luke does not support reals), and we report on solving some benchmarks with floating-point arithmetic from Rockwell-Collins.

Highlights

- Brief introduction to Lustre

- Use Intrepyd to simulate Lustre specifications

- Use Intrepyd to verify Lustre specifications

- Experimental comparison w.r.t. other available software

Keywords

Lustre, model-checking, SMT, Z3, BMC

The Lustre specification language

Lustre is a synchronous dataflow language for programming reactive systems. The language is expressive enough for writing virtually any control software, but its semantic is well defined and conceptually easy to interpret and process automatically (as opposed to a traditional language like C, which is in comparison much harder to deal with). In a typical Model-Based flow, the executable code to be loaded on the actual system can be then automatically generated from the previously analyzed and certified Lustre specification, thus achieving a high degree of confidence on the behavior of the produced sofware.

Lustre is used mostly in avionics and automotive domains, but it finds applications also in nuclear plants and industrial automation. Airbus, United Technologies, Ansaldo, Rockwell-Collins, Schneider Electric, Siemens are just a few examples of companies that employ Lustre for the specification of safety-critical systems.

The following example, counter.lus shows a simple integer counter initialized to 0, and incremented by 1 at each clock tic, unless a reset signal comes to restore the value to 0.

node counter (reset : bool) returns (c : int);

let

c = 0 -> if reset then 0 else (pre c) + 1;

telSemantics of Lustre

The primitive data-types of Lustre signals are machine-precise types:

bool: signals that may assume value 0 (false) or 1 (true);int: integers represented as 32-bits values, same asintof most C implementations;real: single-precision floating-point values, same asfloatof C.

In Intrepyd we interpret the above data-types following the same machine-precise semantics. The same approch is followed in Luke (restricted to the bool and int types). This approach requires using time-consuming algorithms but:

- algorithms are decision procedures (they always terminate);

- non-linear arithmetic can be taken into account.

Other tools, such as Kind2, instead interpret “int” as numbers in Z, and “real” as numbers in Q. The latter approach is certainly motivated by some pragmatic choices, for instance, very efficient algorithms do exists for that setting. But it also has heavy drawbacks:

- non-linear arithmetic in Z is undecidable, only linear arithmetic could be allowed in a design;

- arithmetic in Z never overflows;

- arithmetic in Q does not suffer of rounding and approximations that are typical of floating-point numbers.

In a world where most software failures are due to unseen approximations and overflows we believe that using a machine-precise semantics is of paramount importance for increasing the confidence on the design.

We shall not indulge more on the Lustre language, as there are already a number of resources available online in addition to the ones mentioned so far, such as the PhD thesis of George E. Hagen, or a Lustre course by Philipp Ruemmer.

Analyzing Lustre with Intrepyd: Simulation

We first show how to simulate a Lustre node with Intrepyd. This is useful to quickly take confidence with a specification. The following python snippet is all you need to simulate the node counter above:

import intrepyd as ip

import intrepyd.tools as ts

def do_main():

ctx = ip.Context()

outputs = ts.translate_lustre(ctx, 'counter.lus', 'counter', 'float32')

ts.simulate(ctx, 'counter.lus', 10, outputs)

if __name__ == "__main__":

do_main()Suppose it was saved in a simulate.py, it can be run from a shell with

$ python simulate.py

Simulating using default values into counter.lus.csv

Simulation result written to counter.lus.csv

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

c 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

i0 F F F F F F F F F F FThe simulation trace was produced by using a default value for the input 0 (reset), which is false at every step. The trace was written to a file counter.lus.csv. The values for the inputs can be overridden in the file to provide a different simulation trace. Suppose we set the reset to true at step 3 and 7, we can now obtain the following simulation trace:

$ python simulate.py counter.lus

Re-simulating using input values from counter.lus.csv

Simulation result written to counter.lus.csv

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

c 0 1 2 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3

i0 F F F T F F F T F F Fwhich produces the expected behavior.

Analyzing Lustre with Intrepyd: Verification

Given a Lustre model, a target is a Boolean expression representing a condition on the output of the model that we would like to reach with a simulation trace. Given a target, verification is process of either:

- finding a (finite) simulation trace that evaluates the taget to true at some time step

- proving that no such trace exists.

One of the most successful approaches to verification is model-checking. The basic idea of model-checking is to encode the model and the target into a number of mathematical expressions that are understood and can be solved by dedicated backend tools (SAT-solvers, SMT-solvers). The answers from these solvers can be then decoded back to the original model and combined in several recipies to either find a trace or prove trace inexistence. Here we briefly mention some of these recipies:

- in bounded model-checking (BMC) N copies of the model (with fresh inputs) are connected in series (a process normally referred to as unrolling). If the backend finds values for the inputs that evaluate the target to true than a simulation trace of length N has been found;

- temporal induction (TI), commonly used in combination with BMC to prove trace inexistence. It uses unrolling to construct an induction conjecture that, if proven correct with the backend, constitutes a proof of inexistence for traces;

- interpolation (IMC), and IC3 are more advanced algorithms that iteratively construct expressions representing approximations of the behavior of the systems, which can be used to prove inexistence of traces. During the process of building these approximations the algorithms can also discover simulation traces leading to the target.

In Intrepyd we implement BMC and an algorithm of our own invention, which we called Backward Reachability (BR). BR takes inspiration from the work of MCMT, which we have adapted, chopped and extended to deal with bit-vectors, floating-point arithmetic, and primary inputs. The detailed description of the algorithm is deferred to a future post. For the moment we mention that BR can both find traces and prove their absence.

The following table summarizes some features of the aforementioned algorithms, and shows which ones are implemented in existing tools for Lustre:

| Finds traces | Proves absence | Intrepyd | Luke | Kind2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMC | X | X | X | X | |

| TI | X | X | X | ||

| IMC | X | X | |||

| IC3 | X | X | X | ||

| BR | X | X | X |

Consider the following model counter2.lus which is similar to the previous counter.lus to which we have added a property, wrapped inside a top node. The property is clearly not valid.

node counter(reset : bool) returns (c : int);

let

c = 0 -> if reset then 0 else (pre c) + 1;

tel

node top(reset : bool) returns (P : bool);

let

P = counter(reset) < 5;

telIn the following snippet we verify the design using the BR algorithm.

import intrepyd as ip

import intrepyd.tools as ts

def do_main():

ctx = ip.Context()

outputs = ts.translate_lustre(ctx, 'counter2.lus', 'top', 'float32')

target = ctx.mk_not(outputs[0])

br = ctx.mk_backward_reach()

br.add_target(target)

result = br.reach_targets()

if result == ip.engine.EngineResult.REACHABLE:

trace = br.get_last_trace()

dataframe = trace.get_as_dataframe(ctx.net2name)

print dataframe

print result

if __name__ == "__main__":

do_main()Verification can be run with the following command line. The target is reachable, as expected, at time 5.

$ python verify.py

0 1 2 3 4 5

i0 ? F F F F F

EngineResult.REACHABLEExperiments

In this section we report on some experiments conducted on the benchmark suite of the Kind2 tool, publicly available from here. The suite contains around 900 designs with only one output, representing a property, or equivalently, the negation of a target. Some targets are reachable (design is Invalid) some other are not (design is Valid).

Instead of reporting raw execution times for Intrepyd on the benchmarks, we report a comparison with existing tools.

Comparison agains Kind2

We do not compare against Kind2, because of the different semantics it implements. Would it make sense to compare anyways ? We believe it would not. Take for instance the counter.lus example we used above: in integer arithmetic in Z one can always deduce that, if reset is always false, then c increases at each time step. This is an extremely powerful invariant that, added as assumption to the verification algorithm can be used to conclude a proof immediately. However, in the machine-precise semantics, the invariant is not true, because c will eventually overflow. Unfortunatly many benchmarks in the suite contain counters that could be optimized that way when assuming the integers in Z.

Comparison against Luke

The comparison against Luke is on the designs with bool and int types, because these are the only ones that are supported by Luke. We have run Intrepyd and Luke with a timeout of 300 seconds per each benchmark. Intrepyd is run with BMC and BR algorithms in parallel, while Luke is run with BMC and TI. Experiments can be reproduced by means of the scripts available here.

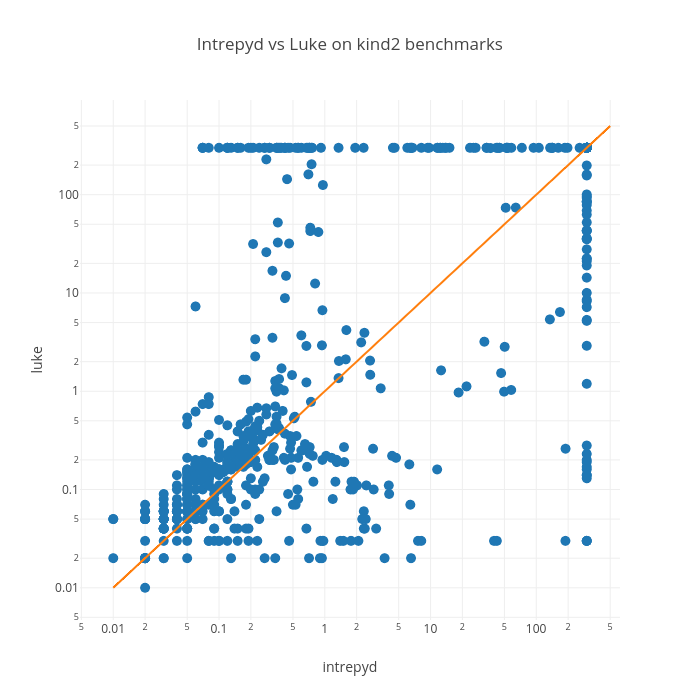

The following scatter-plot reports the runtimes on ALL the benchmarks (except for those in which both tools reported “Timeout”):

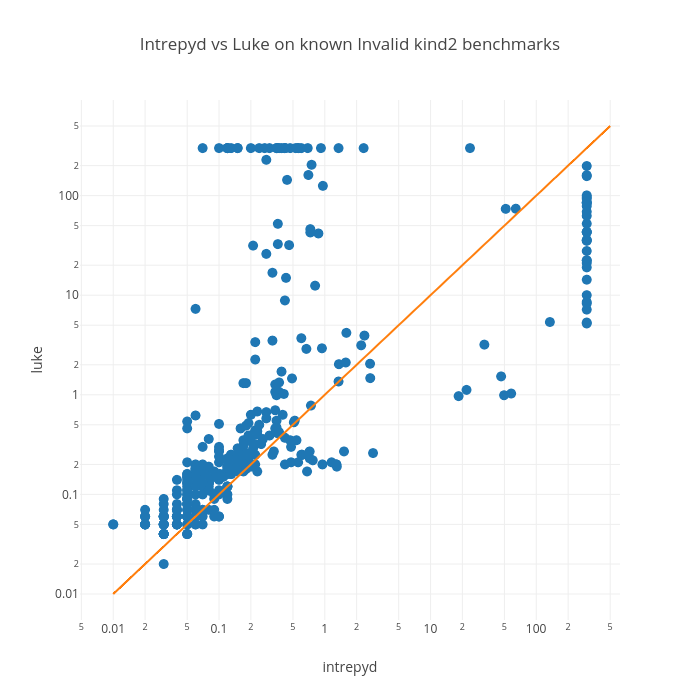

The following scatter-plot reports the runtimes on INVALID benchmarks (those that were reported as Invalid by at least one tool). Basically this is a comparison of the two BMC algorithms of Luke and Intrepyd. The plot indeed shows a similar performance for the two tools, with Intrepyd being slighly faster.

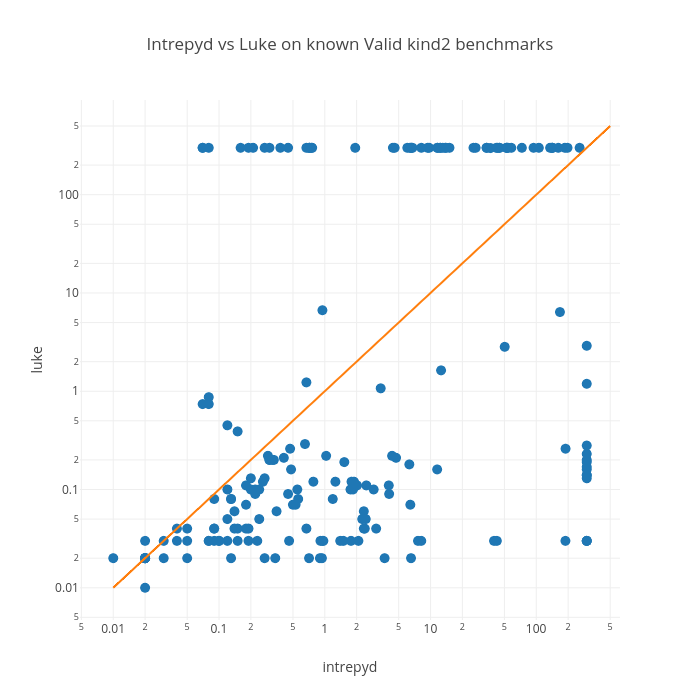

The following scatter-plot reports the runtimes on VALID benchmarks (those that were reported as Invalid by at least one tool). This plot is particularly interesting because it is comparing TI and BR engines (the only two ones that can prove a design Valid in Luke and Intrepyd respectively). We notice that BR is generally slower on small benchmarks, but overall it can solve more designs than TI. We believe that BR can solve those designs that are not provably inductive by TI. This suggests that TI and BR are complementary teqniques. We believe that an implementation of TI in Intrepyd, run in parallel with BR, would be a perfect combo for proving design validity.

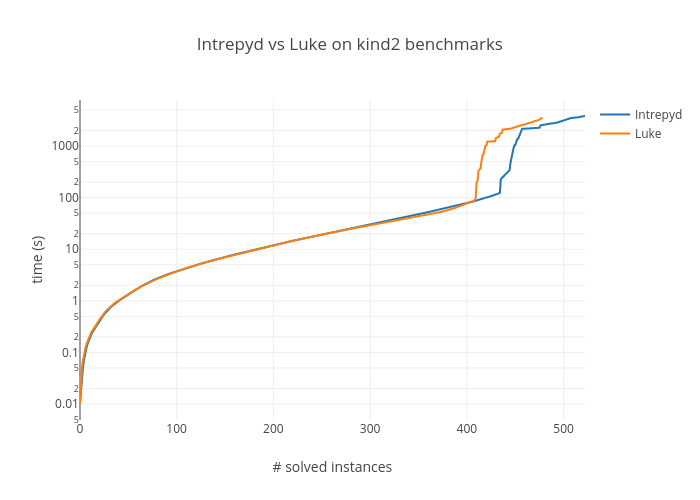

Finally the following plot reports on the accumulated time per number of solved benchmarks:

Designs from Rockwell-Collins

The benchmarks suite contains also some designs that use the real data-type. According to the companion description, these benchmarks come from Rockwell-Collins designs. Because Luke does not support the real type, we just report the runtimes obtained with Intrepyd as follows:

| Benchmark | Status | Time (s) |

|---|---|---|

| large/ccp01.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp02.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp03.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp04.lus | Valid | 6.80 |

| large/ccp05.lus | Valid | 0.07 |

| large/ccp06.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp07.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp08.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp09.lus | Valid | 0.17 |

| large/ccp10.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp11.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp12.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp13.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp14.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp15.lus | Valid | 0.15 |

| large/ccp16.lus | Valid | 0.06 |

| large/ccp17.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp18.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp19.lus | Valid | 0.41 |

| large/ccp20.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp21.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp22.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp23.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/ccp24.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_01.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_02.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_03.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_04.lus | Valid | 7.22 |

| large/cruise_controller_05.lus | Valid | 0.06 |

| large/cruise_controller_06.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_07.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_08.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_09.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_10.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_11.lus | Valid | 0.44 |

| large/cruise_controller_12.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_13.lus | Valid | 0.17 |

| large/cruise_controller_14.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_15.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_16.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_17.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_18.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_19.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_20.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_21.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_22.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_23.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

| large/cruise_controller_24.lus | Timeout | 300.00 |

Conclusion

We have shown the use of Intrepyd for the verification of Lustre designs. We have compared it with Luke on the benchmarks that can be tackled by both tools. Finally we have run Intrepyd on some challenging benchmarks involving floating-point arithmetics, showing that despite the immaturity of Intrepyd, some designs can be already proven correct.